You are here

Semiconductors are Key to Better 3D Printing

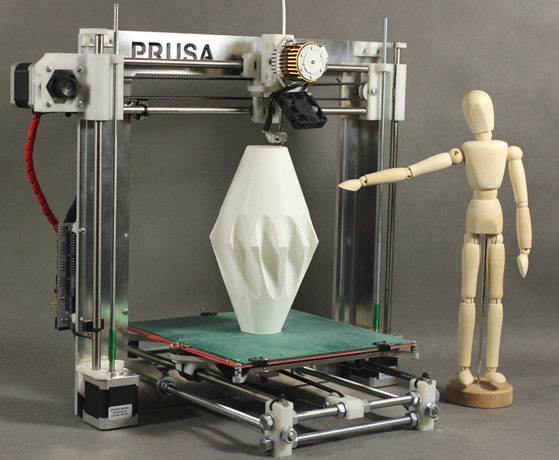

The 3D printing world is an exciting place to be right now. For do-it-yourselfers with an artistic or engineering bent, 3D printing delivers a whole new toolbox, enabling designs that were not possible before with exciting new materials. These DIYers will often build their own 3D printers from scratch. The RepRap movement was formed with the goal of creating a self-replicating manufacturing machine.

The first self-replicating 3D printer was built in 2008 by mechanical engineers at the University of Bath. Since then, the hobbyist 3D printer movement has blossomed from a grad school project to thriving hobbyist community. A 3D printer can be built from scratch using almost any building material (plywood, laser cut acrylic, machined aluminum, LEGO bricks, etc.), however all printers need at least one type of commercially manufactured hardware: electronics.

Example of a RepRap Printer

Source: www.reprap.org

Early 3D printers used Atmel microcontroller development boards (Arduinos) as primary control boards, with discrete stepper motor drivers and MOSFETs. Most implementations used ATmega2560 chips because of their widespread availability. These setups were complicated to build and difficult to expand. Soon, daughter-boards combining terminal blocks, fuses, stepper drivers, and FETs were produced; these simplified the assembly; however, were hard for end users to expand with additional features. The ATmega2560 has much more flash memory than needed to hold 3D printer firmware so, in 2011, a series of purpose-built boards using ATmega644 chips came to market. While identical in architecture and less expensive, the ATmega640 series has considerably less flash memory leaving little room for expansion.

The issue with all of these solutions is the 8-bit CPU architecture and 4-byte limit of floating point decimals. This introduces rounding error into all calculations done by the CPU resulting in hysteresis in the movement of the print head and ultimately artifacts on the printed object. These artifacts hide themselves well on printers using Cartesian movement when printing rectilinear objects, however printers using delta movement often create moiré patterns on the sides of round objects.

Unintended Moiré Effect on a 3D Printed Item

Source: Soliforum.com

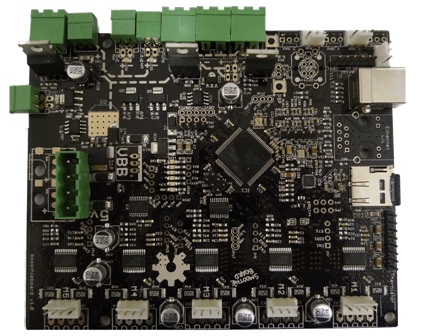

The solution is to use a 16- or 32-bit microcontroller; however, hobbyist development boards with analog to digital conversion and enough GPIOs are rare. The option for 64-bit processing power might be addressed by embedded processors. Intel Atom and AMD have 80x86 MPUs for low-cost embedded control. SoCs based on ARM”s 64-bit Cortex-A53 might be able to address this market. But even mobile SoCs are too complicated and expensive for hobbyist use. Purpose-built motherboards using older and well documented ARM architectures, such as the SmoothieBoard, have recently come to market; however, they have yet to become widely used. A large consumer market potential would spur chip vendors and third party developers to supply controllers, development kits and software tools. Until then this fundamental limitation will continue to create a gap in print quality between hobbyist and professional 3D printers.

Example of a Smoothieboard

Source: www.smoothieware.org

The big 3D printer companies are stepping up their efforts to provide an affordable hobbyist 3D printer for the mass market, but Semico believes the whole premise of a 3D printer is DIY, ‘do-it-yourself’, which means there will always be a contingent of makers who will want the freedom to customize the capability of their printer. The key to the customized 3D printer is ultimately the semiconductor content.

Semico recently released a report on 3D printing titled, 3D Printing: The Next Industrial Revolution, where key success factors for this market are analyzed.

Several key findings include:

- The 3D printing industry will top $3 billion in revenues this year.

- 3D printing materials will grow to be a third of the market by 2019.

- The rise of the Service Bureau and desktop-level printers will democratize design and manufacturing.

- Graphene is a promising future material for 3D printing.

- 3D printer units will grow by 6X between 2014 to 2017.

Check out the table of contacts on our website.

Add new comment